Young People and Transformation Through Theatre

Welcome to the Playing ON blog, a space for the team, our associates, participants and partners to share thoughts, discoveries and resources.

To start the blog we’re going to celebrate some of Playing ON’s key inspirations, and where better to start than with our co-founder, Philip Osment, who would have celebrated his 68th birthday today. Philip very sadly passed away in 2019, though his practice and contributions to the company are still very present in our work today.

In a week where we find ourselves nominated for a CYP Now award for our work with young people on Drilling Diamonds, in partnership with Spotlight Youth Services, it feels a real privilege to share this wonderful piece of Philip’s writing about the power of theatre for young people, written in 2010 not long after the company was launched. This belief in the transformative power of theatre is still at the company's core, whether in our professional productions, engagement projects or training courses.

Enjoy Philip’s words – they inspire us every day.

Philip Osment,

Co-founder of Playing ON

It all begins with our own childhoods. Mine was spent on a farm in a remote rural area of England. I was lonely, bored and had a growing sense that my sexuality meant that I didn’t fit in – I had a shameful secret which I would never be able to share. The isolation that I felt was both geographical and psychological. But then there was the school play: the sense of companionship, shared endeavour, achievement that came from those after-school rehearsals, which even the long ride home on late buses in the dark winter evenings could not dampen. And as I learnt my lines in my freezing bedroom or repeated them to myself in the muddy fields, the words of Shakespeare came alive for me in a tangible way. There was the joy of discovering that someone who lived four hundred years ago could express so beautifully my adolescent inner turmoil:

“But I have that within that passeth show,

These but the trappings and the suits of woe.”

And there were trips to the cinema and sometimes even to the theatre, there were visiting theatre companies who came to the school to perform such new works as Pinter’s “The Dumb Waiter”: enigmatic, ambiguous and inspiring, with its combination of banality and menace, experiences such as this gave me a vision of another world out there – a world of the imagination and of ideas.

I was lucky enough to escape my rural prison through education – I loved learning new languages and ended up studying French and German at Oxford University – but the sense of being different and not fitting in followed me. I had a circle of friends who were loyal and close but there were some things I was not prepared to share even with them. In the rarefied atmosphere of Oxford, there were people who were flamboyantly homosexual who exuded a seeming confidence that I found threatening and – I hesitate to use the word – repellent. I came across them in the hothouse atmosphere of the Oxford University Dramatic Society where driven young people from privileged backgrounds and the odd ambitious grammar school boy vied for status and influence –they seemed to know already that they were future celebrities. I was far too diffident to flourish in such an environment.

A couple of years in London followed where I tried to follow my dream of becoming an actor, eventually gaining a postgraduate place at a drama school. There, I was in my element. I had told a few select friends that I was gay but it was an aspect of myself that had to be concealed – I felt that I would never be allowed to play Romeo if a director discovered my sexuality! At the same time I was beginning to understand that there were wider social and political implications to the whole issue – how could I fail to start to make connections between the plight of gay people and the position of women, Black people, working class people? It was 1976 after all and the feminist and gay movements were gathering momentum.

But the connections I made remained theoretical until I left drama school in 1977. It was my plan to pursue a career as a jobbing actor that would hopefully lead who knows where? To repertory theate? To the RSC? To work in TV? To Hollywood? Then I saw an advert for actors for a new show by Gay Sweatshop – the first professional lesbian and gay theatre company in the UK. Something stronger than the desire for fame and stardom must have been driving me as I auditioned for a part in AS TIME GOES BY, a play about gay history focussing on the Oscar Wilde trials in Victorian London; the fate of gay people in post Weimar Berlin and their incarceration in Concentration Camps; and the start of the modern gay movement with the Stonewall riots in New York in 1969. This was theatre that the audience needed to see, it was telling a story that had been hidden from history, it showed a journey from shame and passive victimhood, to resistance and pride. Audiences across the UK and in Europe gave us standing ovations and the play sparked debate and controversy wherever it was performed. For many people – gay and heterosexual – the play challenged their perceptions of themselves and others, it gave them a sense that they were part of something bigger than themselves. This was transformative theatre.

My work with Gay Sweatshop meant that I had to publicly embrace my sexual identity, that I had to come out to my family. I entered into a long-term formative relationship with Noel Greig who was an inspiration and guide to many people in the alternative theatre movement who was my teacher, mentor, and lover. I count myself lucky to have met people who have imparted rigour, methodology, vision and a demand for absolute authenticity in my work. It hasn’t necessarily made the journey an easy one because it is frustrating when other professionals and critics don’t understand or value the process, but it has made it infinitely richer.

So I have a deeply-held belief that theatre can transform your life – because I know how it has transformed mine. It transforms the participant and it transforms the audience member.

As yet, I have not received the call from Stephen Spielberg and I have never been to Hollywood (although I did translate a play by Cervantes for the RSC a couple of years ago). I have had more than my fair share of success in mainstream theatre as an actor (early in my career) and later as a director and writer. But under the influence of Noel, I have followed where he lead, to work as well with companies such as Red Ladder and Theatre Centre, companies that take theatre into youth clubs, schools, venues that have a commitment to theatre for young people. This work has been infinitely enriching for me as an artist because a well-made piece of theatre that is relevant to that audience has an impact that is tangible.

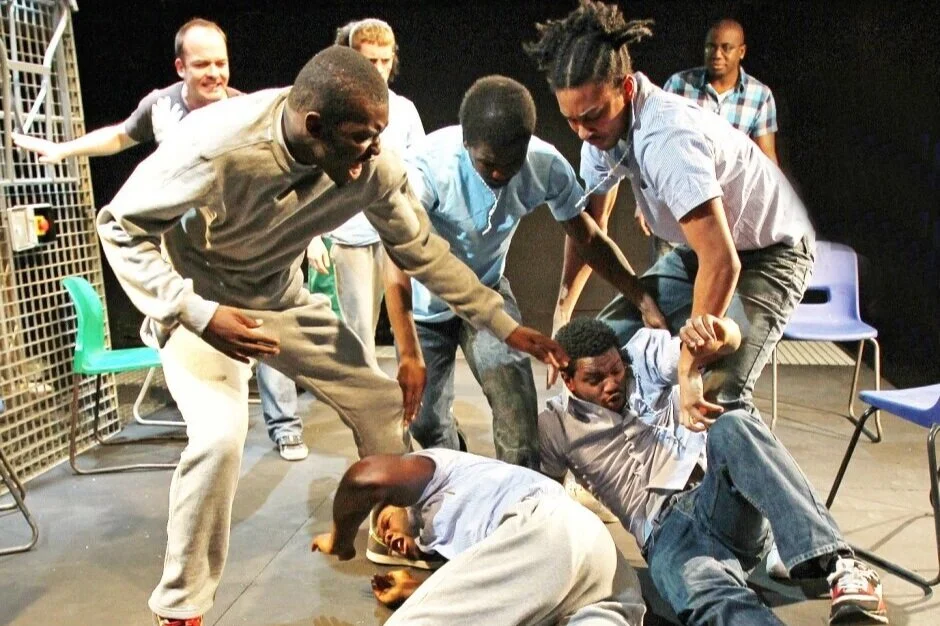

Recently I have become more and more interested in creating work with young emerging artists and have set up a company, Playing ON, to do just that. I became involved with work at the National Youth Theatre where my colleague Jim Pope had set up a course for young people who have experience of homelessness, prison, probation, or who have dropped out of education. For the past three years I have worked with a group of young men from that course to create a piece of theatre about young fathers in prison which has just had a run of sell-out performances at the Roundhouse Theatre in London. I have watched our cast grow in skill and self esteem and become very impressive young men through engaging with the theatre process. They are wonderful role models: one of them wrote in the programme that he wants to open doors that were closed to him, and to leave those doors open for young people behind him. In our after-show discussion I have watched them inspire the young audiences with their articulacy and their authentic acting. And so the process of transformation continues. In one of these post show discussions I found myself telling the audience that the experience of working with this group has been one of the happiest of my life. I don’t know what that tortured adolescent on that farm in Devon would make of it all. He would very possibly have been terrified of those impressive young men and he may have felt he had nothing in common with them. The older me knows better. The older me has been transformed by theatre.